Ending the Isolation of the Upper Cantons of Cerdanya

The story of “the Train Line of Cerdanya” is full of twists and turns, challenges and determination. The train line was born from the crazy project to end the isolation of the upper cantons of the plateau of Cerdanya. Two men were at the origin of the project: Jules Lax (1842-1925), Director of Control of the French Southern Railway and Emmanuel Brousse (1866-1926), both a journalist at the L’Indépendant and an elected representative of the upper cantons (1895-1926).

The story of “the Train Line of Cerdanya” is full of twists and turns, challenges and determination. The train line was born from the crazy project to end the isolation of the upper cantons of the plateau of Cerdanya. Two men were at the origin of the project: Jules Lax (1842-1925), Director of Control of the French Southern Railway and Emmanuel Brousse (1866-1926), both a journalist at the L’Indépendant and an elected representative of the upper cantons (1895-1926).

Between 1901 and 1902, the State, financier of the infrastructures, came to a decision. The train line will go from Villefranche-de-Conflent to Bourg-Madame. The track gauge will be of 1 metre to lower the cost and reduce the radius of curvature. Electric traction, admittedly more expensive than steam, will be chosen, making it possible to consider at the same time the electrification of the region.

It took thirty years (1880-1910) for the Yellow Train to come into existence, finally ending the isolation of the upper cantons of the Pyrénées-Orientales. The difficulties of the route in the mountainous environment and the need for a suitable technical solution explain why it took so long. It is the French Northern Railway Company, ancestor of the SNCF (National society of French railroads), which obtained the concession for the train line of Cerdanya and provided the rolling stock and the staff necessary for its commercial operation.

On the 18th of July 1910, the train section between Villefranche-de-Conflent and Mont-Louis-La Cabanasse was put into service and had immediate success…

On the 18th of July 1910, the train section between Villefranche-de-Conflent and Mont-Louis-La Cabanasse was put into service and had immediate success. The train section between Mont-Louis and Bourg-Madame was operational on the 28th of June 1911. Bourg-Madame was the terminus of the line until 1927, then the Yellow Train line was connected to the French and Spanish Trans-Pyrenean train lines at the train station of Latour-de-Carol/Enveitg. This international train station has the particularity of having 3 different track gauges :

- 1 metre: Yellow Train.

- 1.435 metre: European standard gauge.

- 1.668 metre: Spanish broad gauge.

A “Mountain” Train

The Yellow Train remains an essential means of transport for the upper cantons of Cerdanya because even today, the main road called “Route Nationale 116” is regularly closed due to snow or rockslides.

During the cold season, the snowplough remains available at the train station of Mont-Louis/La Cabanasse. From four o’clock in the morning, the train driver and railway workers clear the way and remove the ice stalactites and stalagmites in the tunnels of the train line.

Numerous Works of Art and Two Remarkable Bridges

There are 650 works of art along the 62.6 km of the train line, including 19 tunnels and 40 bridges.

The most remarkable are, without a doubt, the Fontpédrouse Viaduct (Séjourné Viaduct) and the Cassagne Bridge (Gisclard Bridge), built to avoid unstable ground on the steep slopes of the Têt Valley in this part of the Conflent.

These two bridges commonly bear the names of their engineers/designers, Albert Gisclard (1844-1909) from Nîmes and Paul Séjourné (1851-1939) from Orleans.

The Gisclard Bridge

Commander Gisclard (he was a military engineer) submitted to the French civil engineering administration “Ponts et Chaussées” a project for a suspended metal bridge, an unprecedented system for the railways. At first, this system was considered for the two major crossings of the Têt until Paul Séjourné, famous for his masonry vaults, proposed an elegant granite viaduct.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Gisclard Bridge had a radically innovative design: a non-deforming rigid suspension bridge capable of supporting trains. It was built by the Arnodin company, known worldwide for its metal structures. The achievements of the company – such as the transporter bridges of Bilbao (1893), Rochefort (1899) and Marseille (1903) – were, at the time, as famous as the achievements of Gustave Eiffel.

The Gisclard Bridge is 234 metres long with a slope of 60 mm/m. It crosses the Têt River at a height of 80 metres. The deck passes over the masonry piers without resting on them! This miracle is due to the guy wires and the suspension cables which support it from the metal pylons and stabilize it. The suspension cables are fixed in anchor chambers dug into the rock.

It was repainted in 2009 by a specialized company.

It is the oldest railway suspension bridge in France, the only one still in service, classified as a Historic Monument since the 29th of April 1997.

The Séjourné Viaduct (1906 – 1908)

Paul Séjourné designed many masonry bridges, but that of Fontpédrouse is one of his most original works, a two-storey viaduct with an astonishing central ogive which supports a pier.

The viaduct is 217 metres long with a slope of 60 mm/m. At the lower level, the central ogive with a span of 30 metres crosses over the Têt River at a height of 65 metres. The upper viaduct crosses the Têt Valley thanks to 16 arches. The piers have a decreasing thickness with only 2.5 metres at the level of the deck which, thanks to an innovative use of concrete, can support a platform measuring 4.50 metres.

This work has been listed in the French Supplementary Inventory of Historic Monuments since 1994. According to Michel Wienin, in charge of the inventory of the industrial heritage of the Languedoc-Roussillon, it is the “result of one of the last fundamental research on stone masonry bridges, and we can say that it is in a way the swansong of a bimillennial technique. ”

An Ecological Train Working With Green Energy

The Dam of the Bouillouses Lake

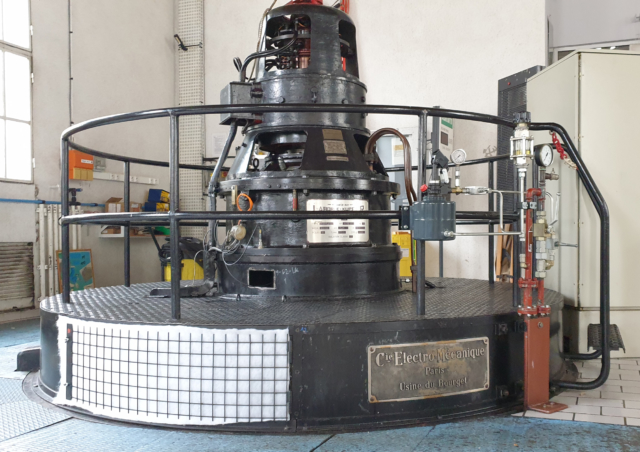

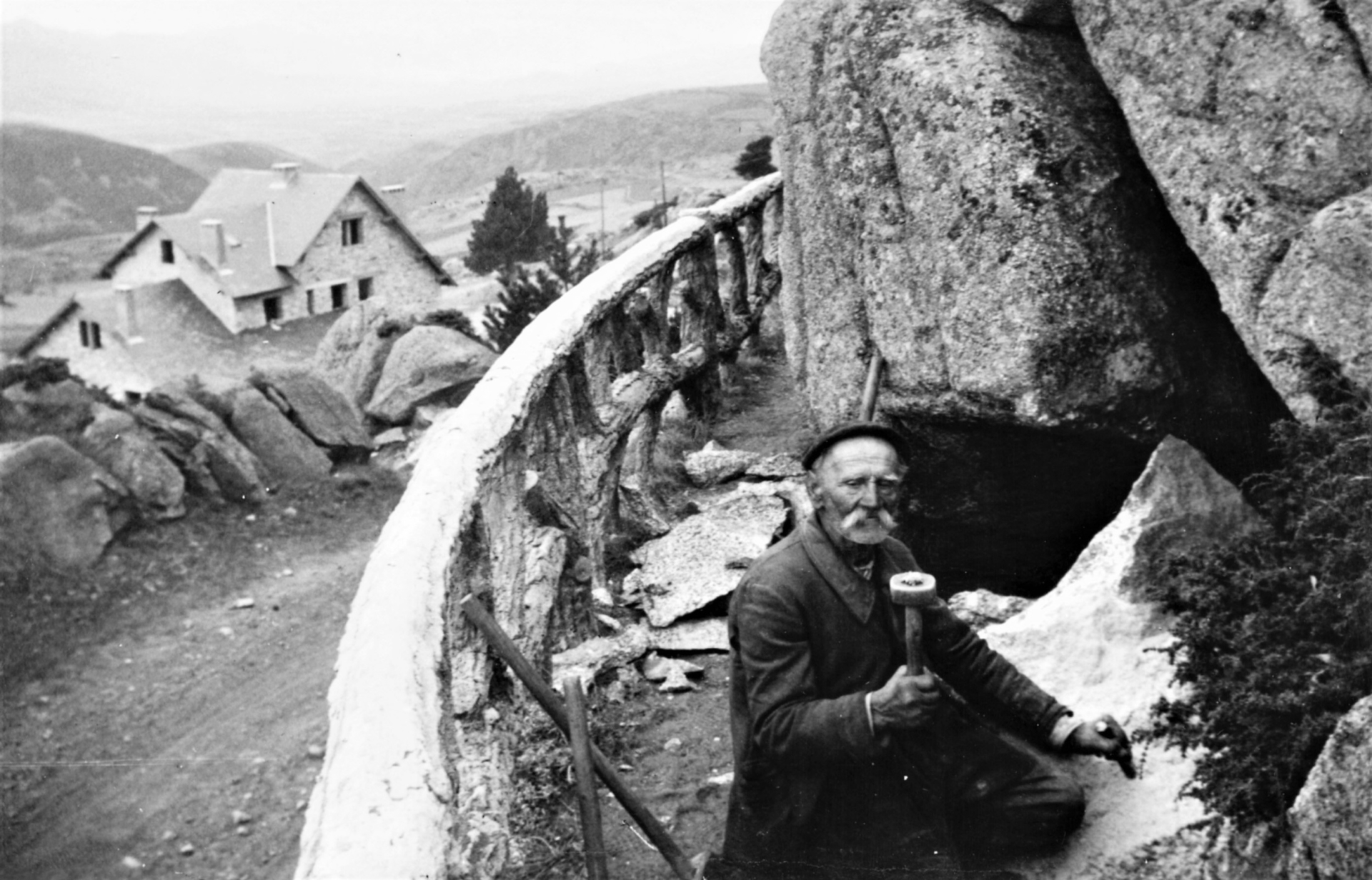

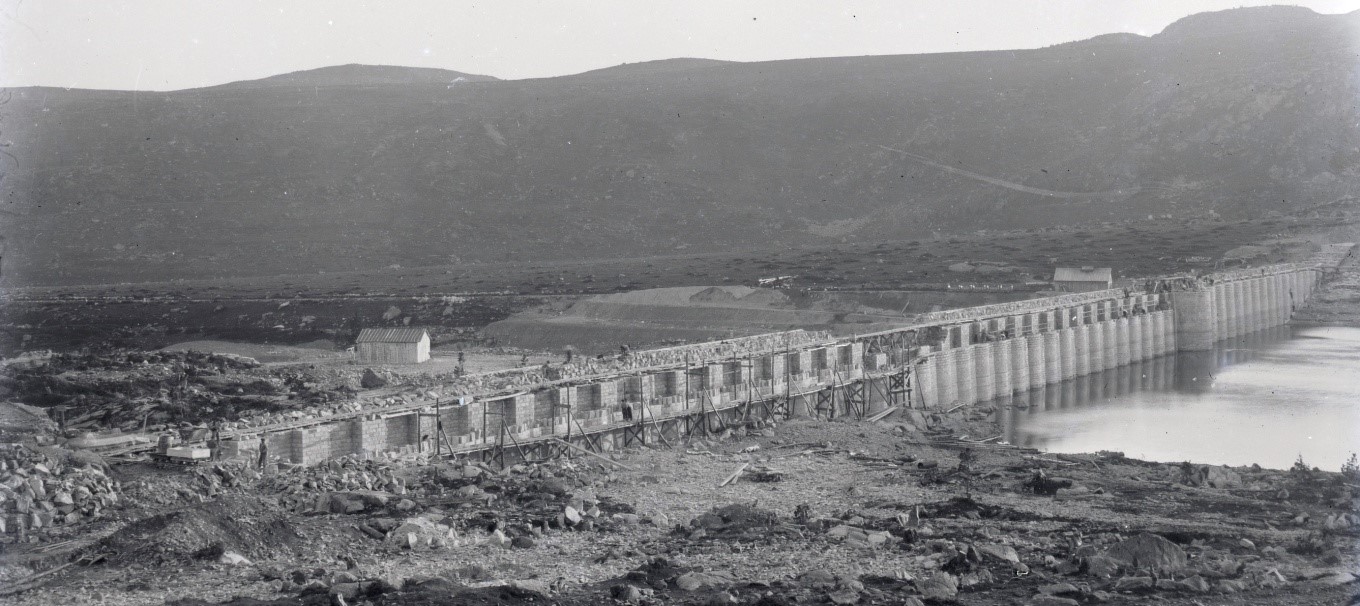

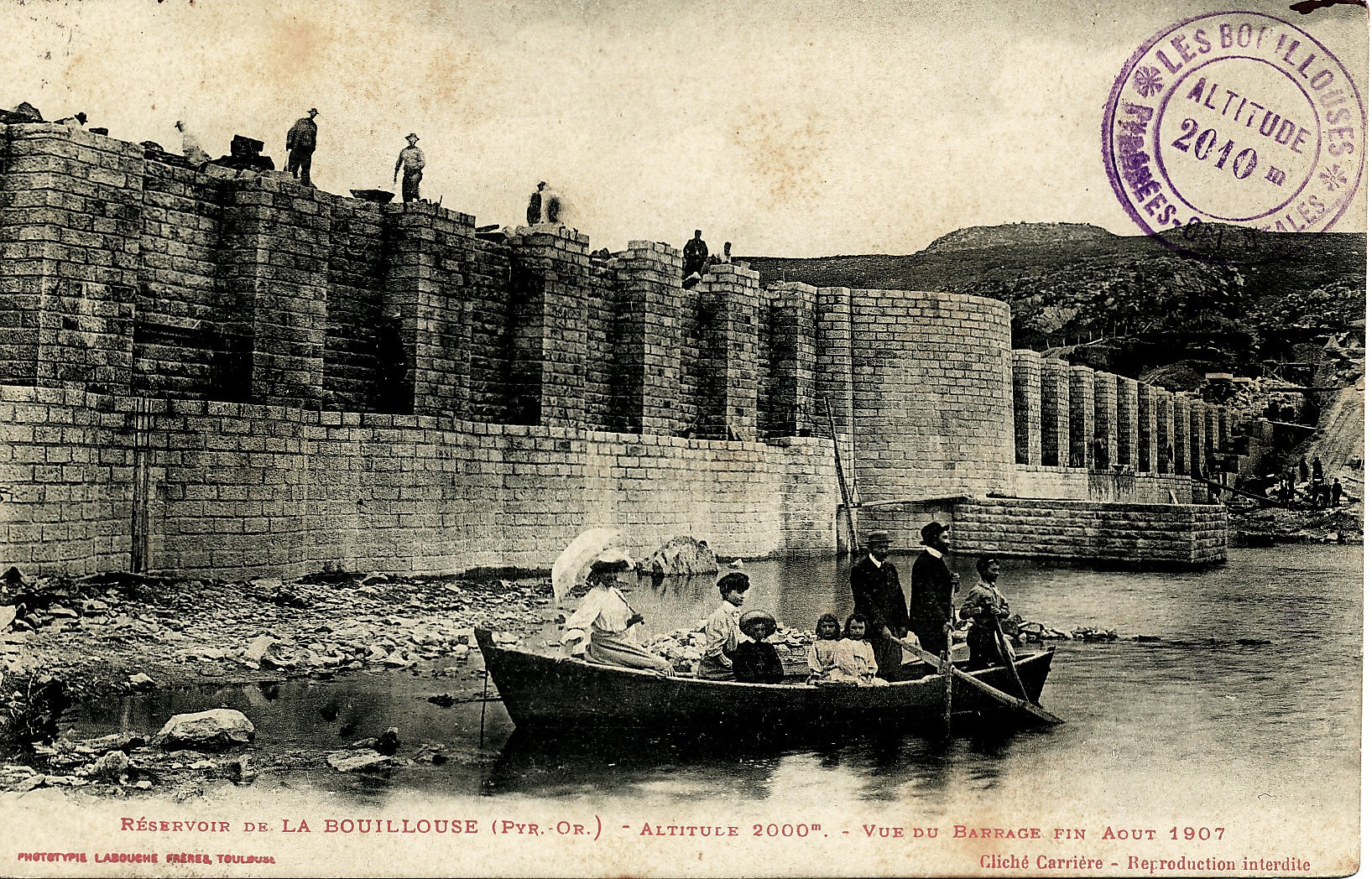

The Bouillouses Dam was built to produce electricity for the Yellow Train. Indeed, the flow of the Têt River was too low and it was necessary to design a reservoir to compensate for the lack of water. The Bouillouses site was found in 1842 by a young hydraulic engineer, Antoine Tastu. The dam, originally planned for watering, was mainly dedicated to the electricity production for the Yellow Train. At the end of the work, the reservoir was handed over to the concessionaire, the French Southern Railway (Compagnie des Chemins de Fer du Midi), then to the French Southern Hydroelectric Company (SHEM) which was then a subsidiary of the National Society of French Railroads (SNCF), currently a subsidiary of Engie. The reservoir initial storage capacity of 13 million m3 was increased to 17 million m3 in 1947. Today, the electricity needed to operate the Yellow Train line is supplied by the national electric system, to which the Têt Valley power plants (SHEM/Engie) are connected.

The Hydroelectric System of the Têt Valley

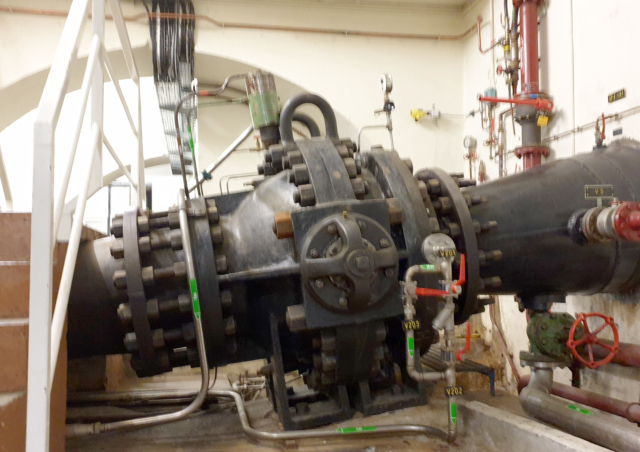

In 1910, the hydroelectric system included the power plant of La Cassagne, the Bouillouses Dam and five electrical current transformer substations which primarily supplied the Yellow Train. The water is drawn from the Têt River, at a place called La Salite, near Mont-Louis.

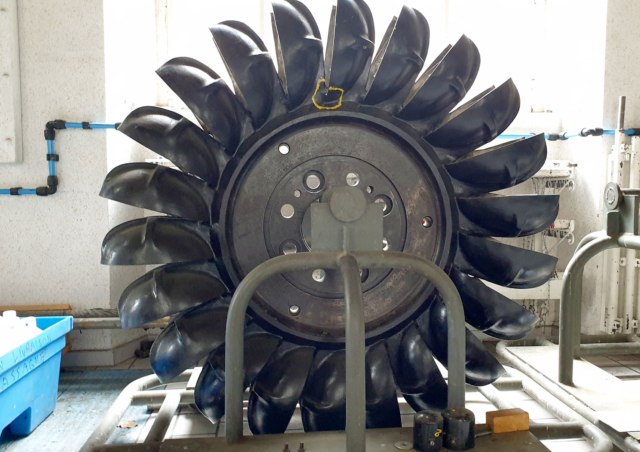

Stored in the village of Sauto in a loading basin (now out of service), the water travels down 420 metres through one-kilometre long pipes to the power plant of La Cassagne. There, the Pelton turbines transform the force of the water into electricity.

In 1913, the power plant of Fontpédrouse was operational. It supplied the train line of Cerdanya and the standard gauge train line between Villefranche and Perpignan. Over the century, six hydroelectric power stations were built along the Têt River in the follower places: Pla des Aveillans (1955), Thuès (1946), Olette (1948), Joncet (1989) and Lastourg (1992), and also one on the river Riberole near the town of the same name (1986).

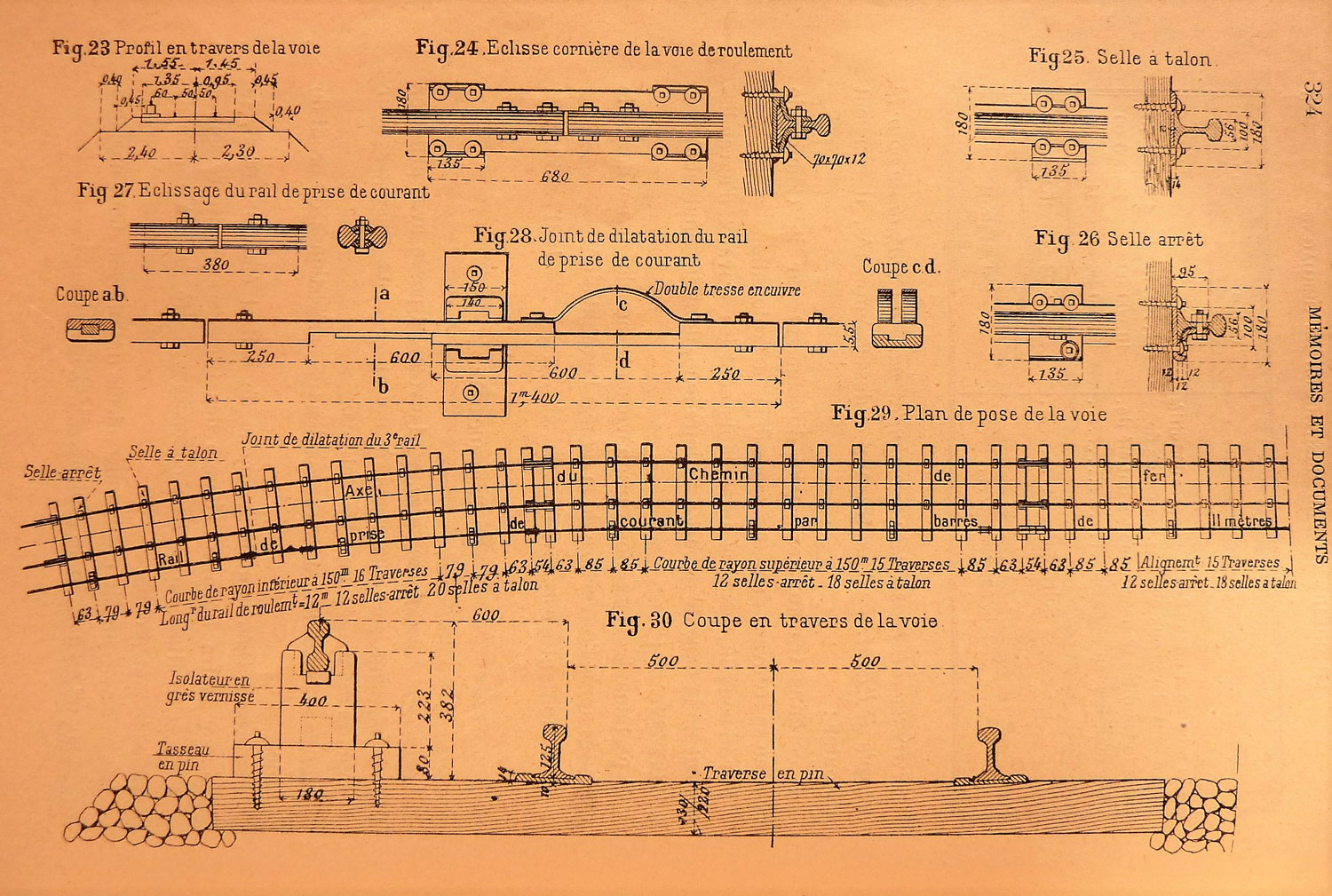

Why a Third Rail?

The Yellow Train is powered by a third rail parallel to the rolling track, called the contact rail. This system, that can also be found in the metro of Paris, was chosen for three reasons: no heightening of the tunnels that would have been needed with overhead lines, better resistance to bad weather and easier snow removal.

The Price of Progress

The Paillat Accident

The inauguration of the train line was scheduled for November 1909, so everyone was busy with the last works. On Sunday the 31st of October, load and stability tests were successfully completed on the Gisclard Bridge.

A first part of the convoy participating in the tests had already left for Mont-Louis. Because of a light rain, the men went into the two remaining railcars towing two flat wagons loaded with rails. A gesture from the driver was taken for a starting signal and the blocks were removed prematurely.

Parked on a 60 mm/m slope, the heavily loaded train drifted on the wet rails. The brakes lacked pressure and the wheels got blocked. The driver lost control of his convoy.

After 500 metres of uncontrolled descent, the two flat wagons derailed and a little further down the two railcars smashed against the side of the mountain at a place called “Paillat”. This tragedy caused a serious injury to nine people and the death of six people: Gabriel Borrallo, François Clerc and Henri Toulet, train drivers; Charles Hubert, Section Leader at the State Railways; Jules Bezault, Assembly-Line Leader at the Arnodin Company and Major Gisclard, Designer of the bridge.

The commission of inquiry concluded that the tragedy occurred because of a braking problem. “If on this day, the train had not left untimely and if, in accordance with the rule, the air brake had been well checked before departure, the accident would not have taken place”. Following this accident, an emergency electromagnetic brake was added to the already existing pneumatic brakes, dynamic brakes and manual brakes.

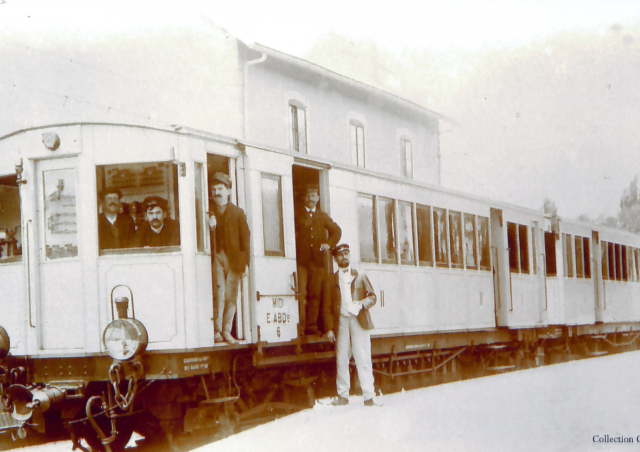

Archive Images

We thank the historians and collectors who hold the rights to these images for their collaboration.

Apprentice Mechanics, Winter 1944 – 1945. Mining Railways…© Cliché Claude Labaume (2003 ) – Cliché Claude Labaume (2003 )

Drawing of the Gisclard Bridge © Coll. Pierre Cazenove – Coll. Pierre Cazenove

Inaugural Train, the Day Before the Accident© Coll. Georges Gironès – Coll. Georges Gironès

Apprentice Mechanics © Cliché Claude Labaume (2003 )

The Gisclard Bridge © Coll. Pierre Cazenove

Train Station Technicians on the Platform© Techniciens de gares sur le quai